Category: Uncategorized

There has been much press coverage on the Navajo Nation’s struggle to contain the spread of COVID-19 on its lands. As of May 2, 2020, the Nation has 2,373 confirmed cases, and more than seventy deaths from the virus. These reports have noted the practical impediments the Nation faces in responding to the pandemic, including a high population of people with pre-existing health problems, the lack of easy access to health care, and the significant number of families without running water.

The Navajo Nation has issued several orders aimed at combating COVID-19. President Jonathan Nez and the Nation’s Commission on Emergency Management declared a state of emergency in early March. President Nez also issued Executive Orders closing the government and the schools. The Nation’s Health Command Center has issued several Public Health Emergency Orders requiring all residents to stay at home, imposing night and weekend curfews, ordering all visitors to leave, closing all non-essential businesses, and mandating the use of masks in public. Finally, the Navajo Nation Council closed all Navajo Nation-owned roads to visitors and tourists.

What is less often discussed is the legal environment facing sovereign Indian nations, like the Navajo Nation, when responding to the pandemic. The Navajo Nation is a sovereign government whose authority pre-exists the federal Constitution. The Nation has two ratified treaties with the United States—from 1849 and 1868—which recognize and affirm the sovereignty of the Nation. Indian tribes possess the common attributes of governmental authority, including the power to issue public health orders. Within their territory, they are the primary governments providing necessary services to tribal members and non-members alike, including combatting infectious diseases.

However, the United States Supreme Court has purported to limit tribal authority in significant ways, classifying tribes not as full sovereigns but as “Domestic Dependent Nations”. In Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the Court ruled tribes have no criminal authority over non-Indians. In Montana v. United States, the Court limited tribal civil jurisdiction over non-members, presuming tribes have no authority, and required them to affirmatively prove one of two exceptions: (1) the tribe must show the non-member has a “consensual relationship” with the tribe or a member, and that the tribe’s regulatory action has a “nexus” to that relationship or (2) the tribe must show the non-member’s actions would be “catastrophic” to the existence of the tribe.

The Navajo Nation and other tribes have pushed back on these limitations, arguing their inherent power to exclude non-members from their lands means they do not have to fulfill the two Montana exceptions. A line of cases in the Ninth Circuit holds tribes may regulate non-members on tribally-owned lands free from Montana’s restrictions. The result is a split between the Ninth Circuit and other circuits over whether the right to exclude, by itself, allows regulation of non-members, with other circuits requiring tribes to fulfill one of the two exceptions. Despite multiple attempts to bring the issue before the Supreme Court, the split remains today.

This legal complexity has immediate practical consequences for tribes’ ability to control the spread of COVID-19. Many tribes have significant numbers of non-members residing within their territory, employed as teachers, doctors, and other occupations, or married to tribal members. Further, due to the allotment of communal tribal lands, some non-Indian families have lived within a reservation for over a century, on lands the tribe does not own, precluding exclusion. Finally, the federal government and tribes have granted rights-of-way within their reservations for public highways. Non-members with no connection to the tribe at all may then enter and travel on the reservation’s highways, and the tribe has no legal right to exclude them .

The lack of clear, compact boundaries further complicates enforcement. Some tribal lands lie outside formal reservations in islands surrounded by state, federal, and private lands, creating a “checkerboard” of land statuses. A tribal public health order may then apply on one parcel, but not on the adjacent one.

Further, some reservations are adjacent to non-Indian “border towns.” The Nation, and other remote reservations, often lack significant numbers of grocery and other retail stores provided by border towns, which incentivizes tribal members to travel off the reservation. Often these communities, such as Gallup, New Mexico, also allow the sale of alcohol when the tribe does not. Travel to and from those towns has increased the spread of the virus and the tribes have no control over whether border towns honor tribal closure orders by closing businesses or restricting alcohol sales.

Because of these issues, tribes are at a disadvantage when issuing public health orders. While states apply their general police powers to all people present in their borders, tribes must constantly fight for legitimacy when doing the same. For some tribes like the Nation, there is very little non-Indian owned land within the reservation, and non-Indians residing there are a small minority who are unlikely to successfully challenge tribal public health orders. However, those tribes may still have issues restricting access on state highways within their reservations, and lack any direct ability to enforce orders in border communities. For other tribes where non-members own their own lands and may be a majority of the reservation population, public health orders may be even more difficult to enforce.

Whether through the power to exclude, Montana’s exceptions, or both, tribal nations should have the authority to restrict movement of anyone within their territory, even on state public highways, especially during a pandemic. As COVID-19 presents a “catastrophic” threat to many tribal communities, tribes can exert the maximum scope of their powers. If non-members challenge such authority, tribes should not hesitate to enforce their orders and defend their actions in tribal and federal court, as the stakes are too high to accept a narrow conception of tribal sovereignty. Given the practical and legal complexities, tribes might also attempt to work with surrounding governments to honor tribal orders, assist in enforcing them, and collaborate on cross-jurisdictional responses to the virus (additional sources on file with author). Through these various approaches, tribes can maximize their resources to fight the pandemic and protect all people within their communities.

Paul Spruhan is Assistant Attorney General for the Litigation Unit of the Navajo Department of Justice. He lives with his wife and two children in Fort Defiance, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation.

While COVID-19 creates profound medical concerns for health care providers, it also creates fear of potential lawsuits. Clinicians are forced to ration scarce resources, such as ventilators, when there is an inadequate supply. Medical professionals describe chaos in hospitals that makes it extremely difficult to treat all patients appropriately. Patients have had elective surgeries postponed indefinitely. Worse yet, some, including cancer patients, have had essential operations cancelled. All of these circumstances could lead to serious patient harm and subsequent litigation.

Medical professionals are worried, and rightly so. At this critical time, however, clinicians should be able to focus entirely on saving lives rather than on concerns about potential lawsuits.

These legal concerns are not new. In 2007, I spent a sabbatical semester at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and worked on public health emergency preparedness in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. I wrote an article calling for comprehensive immunity protections for health care emergency responders. Such protection is more important than ever in the current pandemic.

United States law already provides immunity for some emergency responders. For example, some Good Samaritan laws protect volunteer responders from liability for negligent acts, while the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act provides immunity for the manufacture, testing, and administration of “countermeasures” in pandemics. Countermeasures are products such as drugs and devices that are authorized for emergency use. Federal and state government officials are also protected through qualified immunity, which covers those acting in their official capacities.

But existing emergency response provisions leave a startling gap. Paid health care providers may find themselves without immunity protection for much of the pandemic response work they do. Many providers work at hospitals that are overcrowded and short on supplies. What if they have to choose among desperately ill patients and deny some of them ventilators? What if a patient dies because her surgery was cancelled? What if a doctor mis-classifies someone’s surgery as elective rather than essential? What if doctors are called upon to work outside their areas of specialty or outside of state-of-the art hospital settings? Available protections for these scenarios depend on state law, which are highly variable and inconsistent.

A few governors have heeded medical professionals’ calls for relief. The governors of New York, New Jersey, and Illinois recently issued executive orders with generous immunity provisions.

But this matter is too important to be left up to the discretion of busy governors in the midst of a pandemic. The public health emergency laws of all states should feature comprehensive immunity protections.

The statutes should provide that:

- Health care providers will not be liable for harm caused by good-faith activities in response to public health emergencies.

- Health care providers are covered whether they are volunteers or paid workers.

- Health care providers will remain liable for willful misconduct or gross negligence.

- Protections will be triggered by a state government’s declaration of a public health emergency.

This approach is balanced and would both encourage emergency response work and deter intentional misconduct. Immunity would provide much needed assurance to our overwhelmed and dedicated medical professionals, freeing them to concentrate on their life-saving work without worrying about the legal consequences of their good faith efforts.

Sharona Hoffman is a Professor of Law and Bioethics at Case Western Reserve University School of Law. For additional details see https://sharonahoffman.com/.

Immigrants, those with legal status and those without, individuals returning from incarceration, and individuals with time-consuming childcare and other family obligations often look to start microenterprises like street vending to provide for themselves and their families. However, many municipalities in the United States apply a penal approach to street vending, criminalizing it as a form of vagrancy. Even Los Angeles, a city known for its street vending culture, criminalized the practice outright until 2019. Other cities have permitted vendors to obtain licenses but treat vending in violation of that license as a criminal offense. This continued criminal treatment is taking place even as street vending is celebrated in mediums like Netflix’s Street Food and as cities relax rules for a hip new generation of food trucks.

In the past few years, advocates have pushed to decriminalize street vending around the country. Following the 2016 election, a coalition of street vendors in California successfully pushed to decriminalize street vending statewide. California law now prohibits localities from outlawing street vending outright or treating any violation of street vending regulations as a criminal offense, limiting penalties to administrative fines payable only on an as-needed basis. Meanwhile, high-profile vendor arrests in New York City and Washington, D.C. touched off protests and advocacy around street vending in those cities.

The coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and related closures presented cities with a choice on how to deal with street vending. Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. initially responded to street vendors very differently. Citing the risk that the virus could spread through large crowds gathered at popular vendors Los Angeles city officials called for an effective moratorium on street vending during the crisis. In Washington, D.C., public health clinics approached individual vendors and trained them on becoming “community health ambassadors.” Clinics gave vendors hand sanitizer and other supplies to hand out and trained ambassadors how to teach customers and community members about hygiene and methods to stem the spread of the virus.

These two cities reflect different views of the role and value of street vendors. Los Angeles saw the risk of crowds and took steps to alleviate that risk. The Washington, D.C. approach, on the other hand, sees street vendors as a community asset. Vendors not only provide a valuable service though serving food, they are also integral parts of the fabric of urban communities. “They know when commuters come and go. They know what trends are in vogue, what customers do or do not want. They know which kids are cutting school and how often police patrol.” Now, in a public health emergency, they can be tapped to assist in pandemic response.

Eventually, street vendors in Washington, D.C. were forced home by the city’s stay-at-home order and were unable to continue their public health outreach. Street vendors in both cities now find themselves facing the brunt of the economic consequences of shutdown orders around the country. With their main source of income gone and largely unable to access to small business assistance, unemployment insurance, and other government assistance, these excluded workers are turning to mutual aid networks to meet basic needs.

The laws in these cities treat (or, in Los Angeles’s case, treated) street vending as a vagrancy offense, viewing low-income and largely immigrant vendors as criminals rather than as entrepreneurs. Under this view, vendors are a nuisance, a threat to public health, and poachers of legitimate brick and mortar business. “[W]ithout adequate enforcement, the consuming public was at risk to fraud and health hazards . . . . District Businesses also suffered from this poorly regulated industry . . . . [C]ertain vending carts are not aesthetically pleasing to all or do not align with the aesthetic or historic nature of the neighborhood.” Fostering economic opportunity for vendors and enriching the community by their presence is a secondary concern, and so vending is tightly regulated and often criminalized.

By criminalizing street vending, cities raise barriers to entry for vulnerable entrepreneurs, unduly burden those entrepreneurs most at risk, and detract from the vibrancy of communities. The coronavirus pandemic situation is fluid, and the steps that Los Angeles took may prove to have been necessary to prevent the spread of the virus. That said, the deputizing of street vendors in Washington, D.C. provides a glimpse of a post-COVID-19 world in which vendors are embraced as essential members of urban communities and not a scourge to be regulated away.

Joseph Pileri is a Practitioner in Residence in the American University Washington College of Law. He received his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 2010 and his B.A. from University of California, Los Angeles in 2007.

As the world turns to strategies to stave off the worst effects of the novel coronavirus, now is the time to double down on our commitment to democracy. States around the country are pushing back primary and runoff elections in the hope that, if held at a later time, election procedures can return to the “old normal”. While states can postpone their primaries, they cannot postpone the November 2020 general election.

As COVID-19 becomes a leading cause of death in the U.S., voters will be wary to head to the polls. And, even if the viral effects were to subside, the effects of social distancing will persist in discouraging large-crowd, in-person voting for some time. What’s more, health experts warn that a second wave of the coronavirus is likely to resurface in the United States around October or November 2020. The disenfranchising effect could be staggering if Congress, state, and local leaders don’t act now.

Universal vote-by-mail has emerged as the top policy solution, but states must implement the necessary safeguards to make sure all ballots are counted while also maximizing security and integrity. Unlike in-person voting, the risk of transmission of COVID-19 by mail is nearly nonexistent. Contrary to the warnings of some political officials, voter fraud in vote-by-mail is likely to represent no more than a few thousandths of a percent of votes cast, is generally committed accidentally, and is easily detectable. Public health and security concerns simply aren’t legitimate reasons to object to vote-by-mail.

Indeed, while vote-by-mail is good policy in the best of times, now we have no choice. Yet, constructing a fair and safe vote-by-mail system also demands careful consideration of the available best practices. A thorough review of vote-by-mail options across the country, academic research, and legal decisions on access to voting informed the UCLA Voting Rights Project’s (VRP) nine-point policy report published just weeks ago in response to the pandemic. The report describes how to best protect voters’ health and political voice in November.

First, states must increase access to voter registration by sending all eligible voters a registration form or providing an opportunity to register online. Ballots and envelopes should be uniform in design to catch voters’ attention, be available in a host of languages, and include a paid postage for return. States should implement secure, ADA compliant, and highly visible drop-boxes in current planned polling locations and new drop-box locations like schools, public buildings, and other highly trafficked areas.

If a voter forgets to sign the ballot envelope, or if there is any other mistake, voters should be notified through telephone, text, or email that their ballot has been rejected within seventy-two hours, and those efforts should be recorded. Means of curing ballot discrepancies should include identity verification online or by phone or submission of a replacement ballot and return envelope. Curing periods should last for twenty-one days after election day. Some states already provide similar measures.

Of course, not everyone is able to vote by mail, and for others, particularly African-Americans, voting in-person is a hard-won civic tradition. We should minimize demand for in-person voting while ensuring that the remaining in-person polling locations are structured to responsibly handle crowds of voters and protect the guardians of our democracy, poll workers. These measures should include maximizing the number of polling machines, providing gloves and cleaning supplies to election workers and voters, modifying voting hours for at-risk populations, and classifying election related workers and volunteers as emergency personnel. Just as importantly, states must provide early voting to reduce crowds on election day.

Changing voting procedures necessitates clear communication with voters. In states for which a universal vote-by-mail scheme would be a novelty, states should educate voters about the new system through media outreach. States can even work with USPS to help deliver a notice to register to vote, update voter registration in advance, and provide a reminder to keep addresses current.

Congress has already begun to respond to the need for universal vote-by-mail. While the latest proposed COVID-19 House response bill and Senator Kamala Harris’s VoteSafe Act of 2020 follows many of UCLA VRP’s recommendations, both fall short in the way they address—or fail to address—signature matching as a method to verify voter identity on mail-in ballots. The House bill mandates signature verification to confirm the identity of voters mailing in their ballots; the VoteSafe Act of 2020 contains no provision that requires states to provide an alternative to signature matching verification.

Signature matching involves election officials comparing signatures on file from a voter’s registration or another government record to the signature on their ballot, rejecting the ballot at an official’s discretion. But these election officials are often untrained in forensic handwriting and are rarely given any verification guidelines, so voters can have their ballots rejected arbitrarily. After all, signatures will naturally vary between signings. This is especially true if a state is trying to match an in-person signature to one signed using a computer mouse pad during online voter registration, a practice which the House bill approves. Ballot rejection from signature matching isn’t just arbitrary—it’s also racially disproportionate. Research has documented that strict signature matching guides can disenfranchise young and minority citizens who cast valid ballots. This must be corrected, and our policy recommendations offer a path forward.

Any bill that calls for vote-by-mail must provide reasonable alternatives to signature verification. These include some of the same methods voters already use to verify their identity at the polls and elsewhere, like providing their drivers’ license, passport number, a sworn statement, fingerprint, or utility bill. And because the curing process can take time, the VoteSafe Act’s failure to mandate a fixed time period for voters to be able to cure their ballots grants states discretion to cast away ballots before voters can cure them. Vote-by-mail does not provide an opportunity for voters to exercise their rights if their votes are not ultimately counted.

Any vote-by-mail scheme should include these measures if it is to be safe, secure, and equitable. Given the urgency and importance of the sensible administration of the 2020 general election, states and Congress must act immediately. Vote-by-mail is no panacea, but it’s an important step toward preserving the right to vote amid a national emergency. If our leaders act on these recommendations, it can be even better.

Sonni Waknin and Michael Cohen are Legal Fellows at the UCLA Voting Rights Project. UCLA Voting Rights Project is directed by Matt Barreto, Ph.D., Professor of Political Science and Chicana/o Studies and Chad Dunn, J.D., Director of Litigation, Luskin School of Public Affairs. The UCLA Voting Rights Project continues to monitor access to the ballot amid COVID-19 and is available as a resource for any party concerned with preserving the right to vote. Readers can learn more about the Project here. They can find the Project’s vote-by-mail publications here.

Can a business-closure regulation of commercial property in a pandemic be a taking?

In the midst of a pandemic, it generally falls to government to enact laws and regulations in an effort to curtail the spread of disease. For example, the Supreme Court discusses compulsory vaccination in Jacobson v. Massachusetts and quarantines in Smith v. Turner. In a liberty-oriented constitutional federalist democratic republic like America, this can be challenging–indeed, the volume of published opinions in this area of law show how contentious such health-focused regulations can be when they touch on fundamental rights like bodily integrity, freedom of movement, or property. Our history, our culture, and our Constitution all reflect our heritage of preferring freedom to tyranny. In particular, our nation is founded on the existence and protection of private property. Our property system is, in turn, predicated on the “use” of property. However, private property rights, as with all liberties, are not absolute. Property is regulated by the law, and in many ways, our system is a balancing act between private and public interests.

Thus, whenever the government regulates property use, the question arises whether that action is a legitimate regulation of property for the public good, or whether it “goes too far” and constitutes a “taking” of some property interest. A taking, as classically formulated, is the appropriation of some property interest for the public use. But over-regulation of property can also be a taking. A taking is entirely permissible under our constitutional system so long as the public (through the government) pays “just compensation.”

This is true in good times. And in bad. And right now qualifies as bad.

So, when a government regulates your ability to use your property during a pandemic by forcing the doors of your business to close to the public, can that be a taking?

Yes. But it probably isn’t. But it might be. . .

First, it must be recognized that the Constitution exists even in an emergency. The Constitution expressly permits some alterations to our ordinary system of rights during times of war—for example, the Third Amendment provides differing provisions for the quartering of soldiers in times of peace versus times of war—but those alterations are baked into the system, the Constitution does not disappear in war. And a pandemic is not even a war. At common law, a pandemic qualifies as a time of great public peril. It’s an emergency, but it’s not a war. Thus, the body of law governing causalities of war is not directly on point. Instead, as explained by Chief Justice Hughes in Home Bldg. & Loan Ass’n v. Blaisdell, “While emergency does not create power, emergency may furnish the occasion for the exercise of power.” That is, during an emergency the use of a particular government power may be viewed and analyzed through the lens of the emergency.

In assessing whether a government regulation “goes too far” and becomes a taking of property, Penn Central sets forth a number of non-exclusive factors for consideration by courts. Among these factors is the “character” of the government action. Here, the character will generally be regulations temporarily inhibiting (or completely stopping) ordinary economic use of commercial property for the purpose of preserving actual public health. These measures are designed to be temporary, which will generally militate against liability for a taking. Likewise, the public health has long been recognized as the highest public interest: salus populi suprema lex esto.

Finally, the current regulations closing businesses are generally blanket in nature. No one person or specific class is singled out to shoulder the burden of preventing the spread of the pandemic. One purpose of the just compensation provision of the takings clause is to prevent a private person from bearing a cost to facilitate the public good when that burden should in all fairness be borne by the public. Where the law is of general applicability and burdens all (or most) landowners and property users, it is difficult to see how one (or few) private parties are being unfairly burdened for the public benefit. This parallels to broader jurisprudence analyzing the validity of quarantine regulations to prevent the spread of disease. For example, in Jew Ho v. Williamson that court invalidated quarantine provisions as running afoul of 14th Amendment and as contrary to laws limiting police power when specific quarantine discriminated against one class of persons. This indicates that the broad spread of the pain in business-closure regulation likewise militates against finding a taking. Thus, launching a successful regulatory taking claim in the time of a pandemic seems a daunting task.

I will note a few counterpoints. First, if the government directly acquires property–even during an emergency and even for emergency purposes–compensation is almost assuredly owed under the Constitution and under our common law heritage. Secondly, the Constitution does not exist in a vacuum. The Supreme Court has said repeatedly that there are some contexts in which compensation for losses caused by government action is desirable, or even morally required, even if it does not fit squarely within the mandate of the Fifth Amendment. Finally, the Fifth Amendment is not the end of the inquiry in each state. As the laboratories of democracy, many state constitutions differ from the federal Constitution on when compensation is required–and these variations can only be more protective of private property rights.

On the whole, in synthesizing the general vibe of Penn Central, Blaisdell, Armstrong and the long line of emergency and quarantine cases, it seems fair to say that courts will likely give great deference to the government’s actions that impact land use and property values but do not require just compensation particularly when they are temporary (even if indefinite in duration), are of general applicability, do not confiscate title or permit possession by other people, and are legitimately for the supreme public purpose of directly saving human life. However, even in this time of great public peril, there are no additional privileges or powers created by an emergency. So, the government may (and some certainly will) go too far, resulting in compensable takings of property.

Steven M. Silva is an instructor of Property Law at Truckee Meadows Committee College in Reno, Nevada and a partner at Blanchard, Krasner & French, APC practicing extensively in eminent domain litigation in Nevada and California representing both government entities and landowners. He also served as a staff attorney at the Nevada Supreme Court.

Government surveillance capabilities have always been a matter of public concern, but the current pandemic makes the issue especially salient. We set out to discover what Americans think of government surveillance during this crisis.

Americans have been inundated with media reports of novel forms of public health surveillance since the crisis began. Apple and Google just announced a partnership to create a smartphone contact-tracing application, which would use Bluetooth to trace a person’s movement and contacts. Apple is also using location data from its smartphone Maps application to create “mobility trend” reports that show how smartphone users are moving amidst the pandemic. And who could forget the graphics showing the cellphones of Florida beachgoers dispersing across the country, tracking the locations of thousands of Americans.

Within the public sector, some local health departments, including in Illinois and Ohio, are publicizing data on the number of coronavirus cases by zip code. In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, local police are providing the addresses of infected COVID-19 patients to first responders in an effort to ensure medical personnel use the proper safety gear before entering a home.

Abroad, countries’ efforts to use surveillance technology to combat the pandemic are raising similar privacy concerns. Many countries are using cellphone location data—sometimes GPS, sometimes Bluetooth—to track the movements of infected people and enforce quarantine orders. China, Taiwan, Israel, and South Korea are among the most active in this regard. In Israel, France, and China governments are also using drones to ensure people with COVID-19 are complying with stay-at-home orders. Finally, in Australia, the government is collaborating with a private party to develop a contact-tracing phone application.

The Fourth Amendment requires that government searches be reasonable. This means that you first ask whether an act of government information collection was a “search” (not everything is) and then, second, whether the search was a reasonable one. Warrantless searches are typically unreasonable when undertaken by law enforcement officials to discover evidence of criminal wrongdoing.

Outside the law enforcement context, things are different. Courts assume that it is less problematic and less intrusive to conduct surveillance when the goal is not criminal law enforcement. Rather than immediately imposing a warrant requirement, therefore, courts conduct a reasonableness balancing analysis that weighs the intrusiveness of the search against the expected government benefits of that search. We have seen this analysis employed in the public health context before. In Whalen v. Roe, the Supreme Court held that a state law requiring the state’s health department to collect and keep, but not publicly disclose, patient prescription drug information did not amount to a constitutional privacy violation. The law was plainly useful in accomplishing the state’s legitimate goal of controlling the distribution of dangerous prescription drugs, and the Court thought the risk to patient privacy was minimal given the safeguards in place. Given Whalen, states and local governments might be able to collect COVID-19-infected patients’ information and share it with public health or law enforcement officials, or even private companies aiding in public health efforts, without violating any privacy rights. Warrantless intrusive government data surveillance has been upheld as well in the education and government employment contexts in part on the grounds that those domains are different than law enforcement.

Given the differences in how the law treats public expectations of privacy in the law enforcement versus the public health contexts, we set out to test whether and to what extent these differences affect how people view surveillance on a real public health issue. Are people less concerned about surveillance when it is aimed at fighting a pandemic? We fielded a census-representative survey of almost 1,200 Americans to measure public attitudes towards the use of surveillance under three different conditions: (1) law enforcement collecting information for traditional crime-fighting purposes, (2) law enforcement collecting information to ensure compliance with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, and (3) public health officials collecting information to track COVID-19 infections. Participants were randomly assigned one of the conditions and asked how intrusive they considered various potential searches. The searches were always the same, only the context changed. Data were collected on April 9th, 10th, and 13th. On those three days, a total of 5,471 American deaths were attributed to COVID-19.

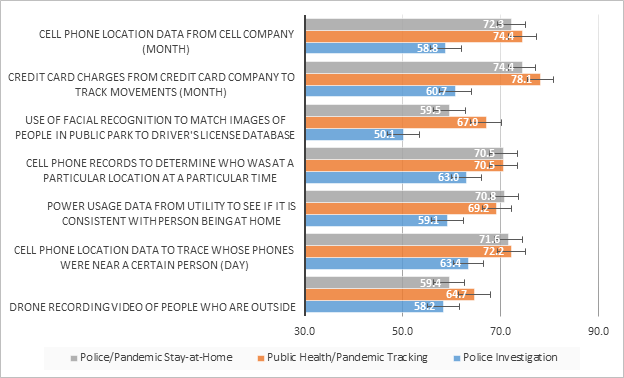

Perceived Intrusiveness of Forms of Government Surveillance by Purpose

Note: Scores measured on an intrusiveness scale ranging from 0–100. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

The survey results surprised us. For six of the seven cases, people were significantly more concerned about surveillance when it was directed at tracking the spread of a pandemic than when used for traditional crime control. This was consistent across three separate measures. The pandemic-related searches were seen as (1) more intrusive and (2) as greater violations of expectations of privacy. People were also more likely to say (3) that government should need a court order or warrant to get the information. For simplicity, we display only the intrusiveness data in the figure.

There are many potential reasons for these results. For one, there is a novelty factor. Whether you like the police or not, we know who they are and what they do when they are engaged in traditional crime control. The idea of public health officials suddenly tracking us, or police enforcing new and pervasive stay-at-home orders, may just be something we are not used to.

For another, the pandemic monitoring scenarios may also imply a more universal form of surveillance. Most often people think of crime-fighting surveillance as directed at people other than themselves. But when it comes to pandemic surveillance, we are all fair targets and privacy violations loom larger when they are directed at you personally. Think of the controversy over the NSA-phone metadata program, which also gathered data on all Americans. Maybe pandemic surveillance just hits too close to home.

Whatever the explanation, our data are striking, and policymakers should consider them when granting enforcement powers. Despite the depths of this crisis, people still found COVID-19 surveillance to be more intrusive than surveillance aimed at general crime control and worthy of greater regulation. At the very least, we should respond to these public privacy concerns by constructing safeguards that limit the uses of pandemic surveillance data and explaining to the public just how we plan to use these data during this new normal. Internationally, we have already seen some movement in this direction. Last Sunday, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that parliament must pass legislation authorizing and limiting COVID-19 surveillance if it wanted to continue monitoring cellphone locations.

Matthew B. Kugler is an Associate Professor of Law at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. Mariana Oliver is a JD-PhD candidate in Sociology.

As a general rule, the government is permitted to restrict activities, including protesting, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government can regulate the time, place, and manner of speech in public forums with a content neutral restriction so long as the restriction is narrowly tailored to “serve a significant government interest” and “leave[s] open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.” A shelter-in-place order can constitutionally prevent public gatherings for a period of time (many of these orders are in effect for a limited period of thirty days) when, as here, a credible body of medical guidance indicates that this potentially fatal and highly contagious virus is more likely to spread and worsen the pandemic during such gatherings, endangering many citizens’ health and lives. Such an order, under the circumstances, clearly serves a significant government interest related to public health.

Similarly, shelter-in-place orders do not foreclose many alternative forms of communication that can be utilized by those disheartened with government action to get their message across. In lieu of gathering to protest in public spaces in contravention of health guidelines, people can express themselves by writing or calling their representatives, flying a flag upside down, circulating virtual petitions, utilizing internet platforms like social media, or writing and publishing op-eds and commentary concerning these restrictions. Much like in Hill v. Colorado—where the Court upheld a Colorado statute restricting speakers from non-consensually approaching anyone within 100 feet of a healthcare facility to distribute literature, engage in oral protest, or to educate or counsel that person—the regulation at issue here is not a regulation of speech, but rather is a regulation of the location where that speech may occur. While the restriction here is more severe than in Hill, under the circumstances, it is almost certainly the case that these many other alternative channels for communication would be “ample” in the eyes of the courts.

In light of this, I anticipate that many of the legal actions being brought on First Amendment grounds by “Reopen” activists to challenge arrests made during recent protests are likely to fail. While political speech challenging government action is no doubt very important, during a pandemic, states have the power—pursuant to the Tenth Amendment—to prevent people from gathering in sizeable groups and standing in close proximity to one another. Acting on this power to address a public health emergency is constitutionally permissible, and I do not anticipate many court rulings to the contrary.

Nicole J. Ligon is the Supervising Attorney and Lecturing Fellow of the First Amendment Clinic at Duke University School of Law.

We need a legal stimulus. Not just a stimulus that is legal, but one that provides legal aid. That is why any further congressional stimulus should allocate additional funds specifically for legal services to individuals who, as a result of COVID-19, face eviction, foreclosure, loan defaults, debt collection, bankruptcy, domestic violence, or denied insurance claims or coverage. The need is dire. These looming crises from the pandemic will hit, but mostly after the initial health scare has dampened, the executive orders are lifted, and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act protections expire or are ignored.

We don’t have to wait to see what will happen—the fallout has already started. Some borrowers, for example, report that their loan servicers, in express violation of Section 4022 of the CARES Act, have informed them that forbearance is not an option; failure to pay will result in foreclosure. While some states and cities pass eviction moratoria, others fail to act. And tenants in locations without eviction protections remain vulnerable not just to eviction but also exploitation by landlords: some, sadly, are demanding tenants pay with their bodies instead of their bank accounts. If this is what’s happening now, just imagine what will happen when the full effects of the pandemic hit.

These crises are solvable, but not without legal aid. The problem is that those most likely to need these services—those evicted, foreclosed, bankrupted, abused, or denied claims—are the least likely to be able to afford it. And, like everyone else, most lawyers—the vast majority of whom work in small firms or solo practices—may be too worried about their own bills to provide counsel to clients who can’t pay. Even with practitioners, law firms, and the American Bar Association providing extra pro bono services, the demand for legal assistance from millions of Americans will far outstrip capacity. That’s precisely why any further stimulus should include funds allocated for COVID-19 related pro-bono legal services.

How do we ensure the legal services reach those who need them? One option is to provide a twelve-month grant, renewable for another twelve -month term, to legal aid organizations and law school clinics that offer free services to individuals. In doing so, we could replicate the method of the original CARES Act, which allocated funds to the Legal Services Corporation, a government-created non-profit corporation, that award grants to non-profit legal service providers. We could expand on this method to provide further funding to pro bono organizations and clinics that hire additional attorneys and staff to perform work related to COVID-19. This approach taps into existing networks of clients—and their contacts—who will likely need services as a result of COVID-19. It also leverages the knowledge and skills of attorneys already providing legal aid to these clients. Attorneys at these clinics and aid organizations can build out capacity by training additional attorneys to absorb excess caseload. Law school clinics also offer a built-in pipeline of new lawyers who have existing relationships with both clients and supervising attorneys. Clinics that hire former students—hopefully including new graduates who have been granted diploma privileges—will require less manpower to train and onboard new employees.

This is not the only option to deliver legal services. We could also scale up existing law firms to handle excess demand or build out new organizations by drawing on local communities of attorneys to address specific legal needs. Finally, we could use other innovative approaches developed by policy-makers.

Whatever its form, this legal stimulus makes sense not only as a proposition for everyday Americans but for the economy more generally. Our economy, in fact, may depend on it. Consider this: When the thousands of evictions and foreclosures do roll in—and they will—who will help renters and homeowners ward off homelessness? Without legal aid, how many families will be forced on the street? How much more difficult will it be for them to obtain employment, or even to eat, without the security of a bed to call their own? When patients crippled by COVID-19 return from the hospital they may be crippled yet again by enormous medical bills, denied claims, and lack of adequate care or medical coverage. How can we expect these people—many of whom will suffer extended recoveries and long absences from work—to contest any medical bills, or even to pay them? When countless patients, individuals, and small business owners go bankrupt, who will help them navigate the bankruptcy laws to allow them to restart their lives? When women who have been habitually abused during lockdowns attempt to separate from their abuser, how will they obtain a restraining order? Without the help of attorneys, many individuals will face daunting legal obstacles—some of which they might not be aware—without a real chance to overcome them.

That is why any further government stimulus should include funds allocated specifically for legal services to individuals who, as a result of COVID-19, face eviction, foreclosure, bankruptcy, domestic violence, or denied insurance claims or coverage. A legal stimulus to these patients, individuals, and families will have significant benefits—both to individuals and to the economy. Most importantly, it will protect the health and safety of millions of Americans by helping them to stay in their homes longer and, in many cases, permanently. Without a safe home, it becomes increasingly difficult to find work, food, or new housing. How can we expect social distancing to continue when people are forced into homeless shelters, or forced to choose between living with their abuser or on the streets? Not only that, but if the housing market collapses, it will wipe out many Americans’ most valuable asset. Millions will lose most of their net worth. The knock-on effects to the economy, as the collapse of 2008 demonstrated, will be devastating.

A legal stimulus also benefits the economy. Providing legal counsel to those in need creates incentives for landlords, creditors, and abusers to abandon or curtail their actions. The incentive to evict and foreclose—especially if those evictions will cost more time and money—will diminish. The same is true for individuals being hounded by debt collectors. Consumers with legal assistance can stave of debt collectors’ attempts to intimidate them into payment, repossess their car, or seize whatever money they have left. At the very least, legal aid may buy them much-needed time and money to get back on their feet. Legal representation may also induce parties to reach an agreement sooner, and at less cost, than would legal action against an unrepresented individual. All of that translates into a better economic outcome, both for the individuals and the economy at large.

A legal stimulus—any stimulus—will face challenges: implementation, waste, administration, delays. But that is a reason to push forward not to pull back. Once we’ve identified the risks and challenges facing any proposed solution, we are better equipped to ensure that the proposed solution is one that works—for everyday Americans and for the country.

Everyone loves to hate lawyers. Some say even Shakespeare liked to tease them in his plays. But lawyers are writing the stimulus, and they’ll be the ones arguing about it for years to come. Lawyers are our worst and best hope. They are what stand between us and the Law of the Streets. We need lawyers—we need a legal stimulus. In a very real way, our future depends on it.

David A. Simon is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas School of Law and a Fellow at the Hanken School of Economics in Helsinki, Finland. Beginning in the fall of 2020 he will be a Visiting Associate Professor and Frank H. Marks Fellow in Intellectual Property, George Washington University Law School. He thanks Brian Frye for helpful comments.

As the coronavirus spreads across the United States, so does an info-demic of dangerous misinformation threatening public health. UN Secretary-General António Guterres characterized this misinfo-demic as a “secondary disease” that needlessly threatens public health, observing that “[h]armful health advice and snake-oil solutions are proliferating.” A U.S. Attorney similarly warned Americans to be “extremely wary of outlandish medical claims and false promises of immense profits.” “[O]ver 4,000 coronavirus-related domains—that is, they contain words like “corona” or “covid” —have been registered since the beginning of 2020. Of those, 3 percent were considered malicious and another 5 percent were suspicious.”

Social media sites are also being used to spread misinformation. For example, postings on the encrypted app Telegram are promoting the dangerous suggestion that ingesting toxic bleach is a miracle cure for COVID-19. President Donald Trump may have been influenced by such disinformation when he “told a press briefing. . . that because disinfectant killed the virus on external surfaces, perhaps it could be injected into the bodies of patients infected with COVID-19 as a treatment.”

The Harvard Health Blog has been tracking “false and misleading posts” about COVID-19 on social media such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok, including the following:

- “[A] false claim that ‘coronavirus is a human-made virus in the laboratory.’”

- “[S]ales of unproven ‘nonmedical immune boosters’ to help people ward off” COVID-19.

- “Unfounded recommendations to prevent infection by taking vitamin C and avoiding spicy foods.”

- “Dangerous suggestions that drinking bleach and snorting cocaine can cure coronavirus infection.”

- A video with dangerous lies such as avoiding cold food and drinks prevents coronavirus infection.

Financial motives underlie many of these viral disinformation campaigns. Right-winger Alex Jones claims “that his Superblue brand of toothpaste ‘kills the whole SARS-corona family at point-blank range.’” Televangelist Jim Bakker is selling “colloidal silver—tiny silver particles suspended in fluid”—as a cure that will eliminate COVID-19 within 12 hours. Recently, a former small-time actor, Keith Lawrence Middlebrook, peddled a fake coronavirus cure to his millions of social media followers while fraudulently soliciting investors. Videos posted to his 2.4 million Instagram followers displayed “nondescript white pills and a liquid injection,” claiming they would offer immunity and a cure.

Other postings appear designed to spread fear and hatred. “Conspiracy theories falsely linking [Bill] Gates to the coronavirus’ origins in some way or another were mentioned 1.2 million times on television or social media from February to April” alleging, among numerous other accusations, that this was a scheme to implant vaccine microchips in everyone.

The problem with these false postings—aside from the fact that they are fabricated—is that some may believe them. By relying upon such fictitious information, people may decide to no longer observe physical distancing, handwashing, surface disinfection, and other preventive measures. They may even die from taking dangerous lies seriously.

In the United States, there is no right to remove dangerous public health misinformation from the Internet because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA § 230). CDA § 230 states: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This brief clause is a liability shield that protects websites for anything third parties create and post online, even if the false information endangers the public.

The majority of federal circuits have interpreted CDA § 230 to establish a broad “federal immunity to any cause of action that would make service providers liable for information originating with a third-party user of the service.” Interestingly, “[t]he legal protections provided by CDA 230 are unique to U.S. law; European nations, Canada, Japan, and the vast majority of other countries do not have similar statutes on the books.”

We believe Congress should amend CDA § 230 to enable the victims of dangerous postings to use tort law to force websites to takedown dangerously false postings about the COVID-19 and similar threats. As with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, websites will have no duty to monitor hazardous public health disinformation. A website operator would be required to expeditiously remove dangerous postings only after receiving notice from government regulators or the direct victims of this incorrect information. Ultimately, this notice and takedown regime will realign U.S. law into conformity with the European Union’s E-Commerce Directive. Our CDA § 230 reform harmonizes U.S. law with the Directive by premising the liability shield for third party content on expeditiously disabling access. This CDA § 230 reform will enable Facebook, Instagram Twitter and other global Internet websites to implement a single notice and takedown procedure, rather than having different policies for the U.S. and Europe.

Michael L. Rustad is the Thomas F. Lambert Jr. Professor of Law at Suffolk University Law School and Co-Director of its Intellectual Property Law Concentration.

Thomas H. Koenig is Professor of Sociology at Northeastern University.

Gun owners and would-be gun purchasers are arguing that state measures to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus infringe on their Second Amendment rights. To the extent the premise is correct—the Second Amendment guarantees access to a firearm store—it’s not clear that their conclusion follows.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, forty-five states have issued statewide stay at home orders. These orders are based upon guidance from the Center for Disease Control and other public health agencies that have identified social distancing as the best tool to limit the spread of the coronavirus. Most of the orders include, among other things, provisions calling for the closure of all but “essential” businesses, prompting a common question: What constitutes an “essential” business?

Most states include in their list of “essential” businesses hospitals, grocery stores, pharmacies, and infrastructure services (e.g., plumbing). The NRA and other similar organizations have been challenging the definition of “essential” in the states that do not include gun stores in the definition. The plaintiffs—first-time gun owners—argue that the state’s action makes it impossible for them to exercise their constitutional right.

The argument is not new. There are countless cases where individuals have challenged government conduct on the basis that their property right is burdened or destroyed by a regulation or by direct government action. Such action, the argument typically goes, constitutes a taking. There are numerous parallels between the right to keep and bear arms and property rights. Among other things, most courts understand both rights to be fundamental, individual rights that prefigure ratification, are subject to bright-line rules, and their respective doctrines often place an emphasis on history and tradition. Additionally, as I argue in an article forthcoming in the William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, property principles arguably inhere in the Second Amendment, and takings doctrine has particular relevance in certain areas of Second Amendment jurisprudence. Thus, takings law could similarly be instructive in the context of the recent gun store closure orders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We know that since before the founding, courts have affirmed government action burdening—or in fact destroying—an individual’s property right. This notion is even more true in moments of crisis like war and pandemics. For example, in Seavey v. Preble the Supreme Court of Maine permitted state physicians to destroy homes believed to harbor the smallpox virus. The court noted the government’s conduct was a “gross outrage,” but because there was a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the science of the disease, the court recognized the state was within its authority to take action it believed necessary to protect public health. Even if that meant infringing on a fundamental, independent, constitutional right. More recently, in a landmark takings case—Miller v. Schoene—the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Virginia’s order destroying particular privately–owned trees throughout the state, as the trees were known to carry a disease that threatened the state’s apple industry.

These are just two examples. But both cases, and others like them, share a common feature: where the state acts to preserve the public health and welfare, but in so doing burdens an individual right, lawful government conduct is typically tailored towards the source of harm or health risk. In Seavey the government action was focused on the property rights of the homeowners whose dwellings were infected. And in Miller the order was focused on the cedar trees that likely carried the infection—not oaks or pines. In the COVID-19 context, current expert guidance suggests that everyone is a possible vector of the disease. Physical proximity is a grave concern because anyone can both contract and transmit the virus. The stay at home orders are crafted with this in mind. Permitting opportunities for individuals to come into close contact with others who may be infected presents tremendous risk. States have thus far responded by limiting those opportunities to only vital businesses and services.

Similarly, there are cases where the government has prohibited access to an individual’s property to protect public health, morals, and welfare. Here, too, individuals challenge the action as a violation of their individual right. For instance, in Andrus v. Allard the federal government prohibited the sale of eagle feathers. The Court affirmed the regulatory action was no taking. Necessarily implied from the “right to sell” is the “right to buy,” but in both instances the Court concluded that the right is but a single strand in the bundle of rights, and burdening a single strand does not constitute a violation. Recall, the Court told us in Heller that the core Second Amendment right is self-defense. In the challenges brought against state stay at home orders, many plaintiffs argue that they do not feel safe during the pandemic and that the orders are infringing on their Second Amendment right. Self-defense does not require a firearm. Whereas, for example, without access to an abortion provider, how does one exercise their right to abortion? This is, arguably, one way to distinguish the orders prohibiting access to abortions from orders prohibiting access to gun stores.

Additionally, temporary or non-substantial burdens on access to one’s property are typically permissible. The state orders do not suspend the ability to defend oneself; they temporarily pause the ability to purchase firearms in a store. Many of the state orders closing all non-essential business include sunset provisions: they elapse at a certain date. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court relied on this temporal reasoning in its decision last week rejecting a takings challenge to the state’s stay at home order. Every state that has implemented a stay at home order thus far has indicated the closure of non-essential businesses is a temporary act tied to flattening the curve. This suggests that such temporary burdens on the Second Amendment right similarly do not trigger constitutional protection.

It is important to note that the questions surrounding whether gun stores are “essential” businesses and whether states can close them sit at the intersection of law and politics. Thus far, the states that have reversed their decision and added gun shops to the list of “essential” services have not done so under court order. Instead, the challenges have primarily been litigated in the court of public opinion, which illustrates an important takeaway: it’s not the Second Amendment that is doing the work to change the states’ position. Not the “judicial” Second Amendment, anyway.

Adam B. Sopko is a student at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law and the Editor-in-Chief of Volume 115 of the Northwestern University Law Review.